The History of Cheese Making in Kawartha Lakes

2012.FIC.38 cheese stencil. The Pine Grove Cheese Factory in the former Ops township in operation from at least 1898 and likely ceased operations permanently in 1911 when it was put up for auction.

Early settlers brought the art of making butter and cheese with them, since they didn’t have methods of refrigeration and wanted to extend the shelf life of their cow’s milk. Butter and cheese were made by the women of the household, who, after supplying the needs of the family, ' traded' the surplus for groceries and other requirements. Production was limited to the amount of labour which the farmer's wife and daughters could spare from other arduous duties. Making cheese is not a quick process and did not become a lucrative business until production moved to the factories.

The first cheese factory in Canada began production in 1864 in Oxford County. This method of pooling resources quickly caught on with Ontario farmers and spread to Kawartha Lakes where cheese factories began to form by 1870. Over the next twenty years, there would be at least one cheese factory in every township.

Although equipment existed for separating cream from milk by 1896, no creameries or butter factories had been built yet, but there were 16 cheese factories.

Those first cheese factories:

Palestine

Lorneville

Maple Leaf (Downeyville)

Omemee

Cambray

Cameron

Little Britain

Mariposa

Valentia

North Ops

Reaboro

Bobcaygeon

Dunsford

North Verulam

Red Rock (Verulam)

Star (Scotchline/Bobcaygeon)

The Cheese Factory Act

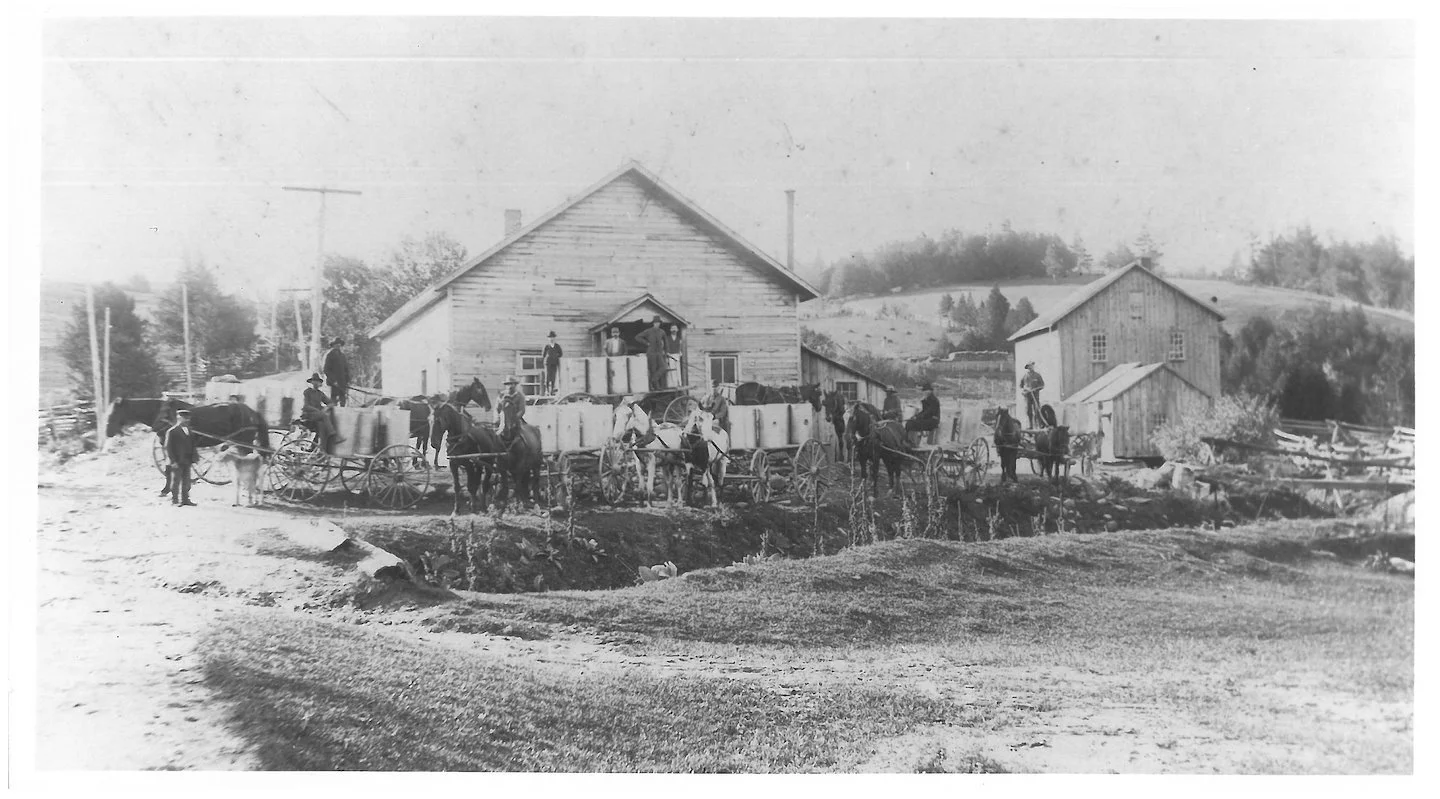

2023.89 Dropping off milk at the cheese factory. Location unknown.

Ontario enacted the Cheese and Cheese Factory Act to encourage cheese co-operatives. Groups of fifty or more farmers who lived near each other would draw up an agreement that followed the guidelines in the Act, register their co-op with the county registry office, and appoint a management committee. Money was pooled to construct a factory and equip it with the necessary supplies and equipment. Often the provincial government helped subsidize start-up costs. Then the farmers supplied the milk and hired a cheesemaker.

Careful records were kept of the milk that was dropped off. The cheese factory produced and sold the cheese to customers, and then the profit was distributed to the farmers, the amount of which corresponded to the amount of milk supplied.

Breach of the Cheese and Cheese Factory Act did happen on occasion, as three men found themselves facing such a charge in 1898 at the county courthouse. Robert Wilkinson, Philip Barker and Henry Copeland were assessed fines payable to the Dairyman’s Association in amounts equivalent to about $1000 today.

Diary? Creamery? What’s the difference?

The legal definitions according to the Government of Canada’s Department of Agriculture as defined in 1911 is as follows:

“Creamery” - a place where milk or cream from not less than 50 cows is manufactured into butter;

“Dairy” - a place where milk or cream from less than 50 cows is manufactured into butter;

“Butter” - the food product known as butter manufactured exclusively from milk or cream or both, with or without the addition of colouring matter, common salt, or other harmless preservative;

“Creamery butter” - is butter manufactured in a creamery;

“Dairy butter” - is butter manufactured in a dairy;

“Whey butter” - is butter manufactured from whey;

“Milled butter” - is butter that consists of a mixture of creamery butter and dairy butter, or of two or more lots of dairy butter that have been manufactured in different dairies and mixed together;

“Cheese factory” - a place where cheese is made;

“Butter factory” - a place where butter is made.

The definition of “creamery” and “dairy” evolved to mean a larger factory with cold storage where milk, cheese, butter and ice cream were manufactured.

Making Cheese

Cheese factory at Cameron. Photo from Kawartha Lakes Public Library.

At six in the morning, farmers drew their milk, loaded it onto a wagon, and drove it to the cheese factory. When the farmers did the nightly milking, they cooled the cans in water, stored them overnight in the cellar, and then took them to the cheese factory with the morning’s milking.

Cheese factories were erected next to streams for the fresh water required for the cheese-making process. A wooden frame building was constructed on a stone foundation, the interior divided into a storage room and the curing room. Basement space was also required for storage, where the temperature could be better controlled. Temperatures higher than 16-degrees Celsius in the curing room resulted in faults in the cheese. Temperatures over 21-degrees Celsius resulted in a disagreeable flavour. In 1902, the Department of Agriculture recommended that curing rooms could be improved by thoroughly cleaning with a blend of boiling water and carbolic acid and then white-washing with fresh slaked lime. If there were gaps between floor boards, it was recommended to cover with two layers of building paper before putting down a fresh floor. The walls and ceilings should also have been given two layers of building paper and fresh lumber to help insulate from the summer daytime heat.

Photos of interior of cheese factory from An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Dairy Industry of Canada. J.A. Ruddick. 1911.

Bert Lee of Bobcaygeon became the chief cheesemaker at the Red Rock cheese factory in July 1920 at the age of 19, after apprenticing at the Bobcaygeon Cheese Factory. When Lee was attending Agricultural College in Guelph, he made the following notes:

“Care of milk. Cows should be clean, and barns kept free from dust. Morning milk must be cooled to 60-degrees before mixing with last evening’s milk. Milker should wash his hands before milking, and milk should be strained through two or three thicknesses of cheesecloth. To make a culture that would start fermentation in a vat of milk, use milk from the same source all the time. To tell when the curd was ready to cut, insert forefinger at a 45-degree angle, break the curd slightly with the thumb then slowly lift finger.”

Over the course of three to four hours, the milk was churned in vats that were powered by steam, separating the curds and whey. The whey was churned into a cheap butter and the leftover whey was returned to farmers to feed to pigs. The curds were washed with fresh water, then salted and washed again. Next, the curd was put into a round press, packed and cut into standard sizes of about sixteen inches in diameter. Any cheese that wasn’t bought by the local community was loaded onto trains and sent to markets.

Cheese Business

The shipping of cheese by train (and by 1902 to the United Kingdom) created the need for proper-sized boxes to secure the cheese wheels. The Ryder and Kitchener Company, located on the Scugog River at Ridout and Russell Streets, made such crates for the local cheese factories until their mill burned in October 1907.

The revenue farmers generated from the cheese factories allowed them to build brick homes and bank barns. In 1900, the Linden Valley cheese factory posted profits from butter manufacturing at $22.74 and from cheese at $291.75 (an estimated equivalent of $11,000 today.) In 1861, Kawartha Lakes had 6725 cows that produced 16,939 lbs of cheese. By 1901, the number of cows had grown to 21,865 with a production of 1,545,545 lbs of cheese. In 1897, 15 million pounds of milk had been supplied to the county’s cheese factories. The resulting cheese had been sold to 1047 customers with net returns of $95,954. Business was booming.

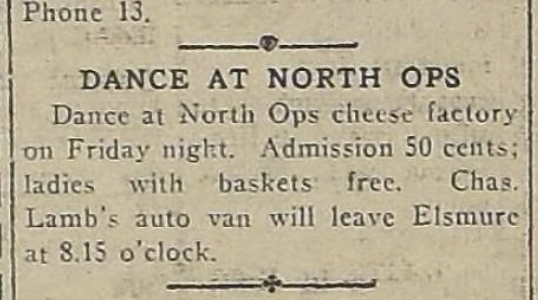

from The Lindsay Post, September 7, 1921.

Dance halls didn’t exist until the mid-1900s, in fact, dance halls likely came about because of the demise of cheese factories, since social functions were once held in cheese factories. A pie social was held in the North Ops Cheese Factory in March 1919. In 1930, the North Verulam Cheese Factory was the site of a big dance in honour of a bride and groom. And of course, the cheese factory served as the meeting hall for the members of the co-operative.

“Tons of melted cheese, butter, lard, and eggs flowed from the building, across the railway tracks, down the riverbank, and into the Scugog River like molten metal.”

Lindsay Post, October 5, 1916

In 1966, Frank O’Connor recalled the disastrous fire at the Dundas and Flavelle Cold Storage in Lindsay that occurred on October 5, 1916, when “tons of melted cheese, butter, lard, and eggs flowed from the building, across the railway tracks, down the riverbank, and into the Scugog River like molten metal.” The Lindsay Post reported the melted cheese covered the surface of the river for some distance. But Flavelle recovered, constructing their cold storage and creamery business at the corner of Kent Street and Victoria Avenue.

By the 1950s, Kawartha Lakes no longer had cheese factories in operation. Consolidating small cheese factories into larger creameries (where milk, cheese, butter and ice cream were made in buildings cooled by blocks of ice) became the fashion of businesses at the time, and although the Kawartha Lakes cheese and butter factories held out against consolidation longer than neighbouring Peterborough, eventually, they folded. With pressure from foreign buyers wanting cheese of uniform texture and taste no matter the unpredictable Canadian weather, those with the means of building larger buildings with better insulation and colder storage fared better. By 1964 only two creameries remained in the south half of the county: Briar’s Dairy in Lorneville and Silverwood’s Dairy (previously Flavelle’s) in Lindsay. (In the north half, Kawartha Dairy started in 1937 when the Crowe family bought a small dairy in Bobcaygeon. The Fenelon Falls creamery consolidated into Briar’s Dairy in 1961.)

Star Cheese Factory at Scotch Line. Copy of sketch from Kawartha Lakes Public Library. Original remains with the Thurston family.

After the cheese business consolidated into creameries, the cheese factories were left empty. Most of these buildings deteriorated over time since they were of basic wooden frame construction. Several were purchased and moved from their original locations to serve as storage buildings. Some were lost to fire. Three buildings remain standing today but have been heavily renovated and are privately owned:

Lorneville - 1264 County Road 46

Bobcaygeon - 76 North Street

Omemee - east side of Queen Street not far from Distillery Creek

Where once the Kawartha Lakes was a thriving and award-winning area for cheese making, the industry had dwindled away until Mariposa Dairy began operation in 1989 and today continues to make goat cheese that is sold around the world.

Learn more about the trials and tribulations of building a thriving dairy business from the ground up in our online exhibits:

Resources:

Blythe Women’s Institute Tweedsmuir History.

Illustrated Atlas of the Dominion of Canada. H. Belden & Co. Toronto, 1881.

Kawartha Valley Women’s Institute Tweedsmuir History.

Kirkconnell, Watson. Victoria County Centennial History. Watchman-Warder Press. Lindsay, 1921.

Knox, Jennifer, Lloyd Junkin and Joan Knox. Verulam View. Kingston, photocopy by Lake Ontario Regional Library, June 1980.

Ops School-Section Map. December 1898.

Ruddick, J.A. An historical and descriptive account of the Dairying Industry of Canada. Department of Agriculture. Ottawa, 1911.

Times Gone By. Dyson & Freeborn. nd.

Lindsay Post:

April 9, 1875

April 12, 1902

June 4, 1907

October 21, 1907

October 5, 1916

September 4, 1930

March 23, 1955

April 26, 1966

September 23, 1967

Warder:

May 15, 1891

March 1919